- Home

- Damion Searls

The Inkblots

The Inkblots Read online

Copyright © 2017 by Damion Searls

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Hogrefe Verlag Bern for permission to translate the essay Leben und Wesensart by Olga Rorschach, from “Gesammelte Aufsätze,” Verlag Hans Huber, Bern, 1965. All rights reserved. Used with kind permission of the Hogrefe Verlag Bern.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Searls, Damion, author.

Title: The inkblots : Hermann Rorschach, his iconic test, and the power of seeing / Damion Searls.

Description: New York : Crown Publishing, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028995 (print) | LCCN 2016042118 (ebook) | ISBN 9780804136549 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780804136563 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780804136556 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Rorschach, Hermann, 1884–1922. | Psychiatrists—Switzerland. | Rorschach Test.

Classification: LCC RC438.6.R667 S43 2017 (print) | LCC RC438.6.R667 (ebook) | DDC 616.890092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028995

ISBN 9780804136549

Ebook ISBN 9780804136556

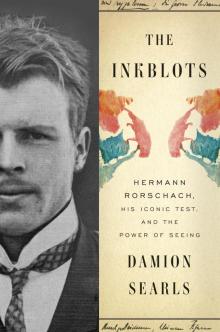

Cover design: Elena Giavaldi

Cover photographs: (inkblot) Spencer Grant/Science Source/Getty Images; (Rorschach and handwriting) Archiv und Sammlung Hermann Rorschach, University Library of Bern, Switzerland

v4.1_r2

a

The soul of the mind requires marvelously little to make it produce all that it envisages and employ all its reserve forces in order to be itself….A few drops of ink and a sheet of paper, as material allowing for the accumulation and co-ordination of moments and acts, are enough.

—PAUL VALÉRY, Degas Dance Drawing

In Eternity All is Vision.

—WILLIAM BLAKE

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Introduction: Tea Leaves

1 All Becomes Movement and Life

2 Klex

3 I Want to Read People

4 Extraordinary Discoveries and Warring Worlds

5 A Path of One’s Own

6 Little Inkblots Full of Shapes

7 Hermann Rorschach Feels His Brain Being Sliced Apart

8 The Darkest and Most Elaborate Delusions

9 Pebbles in a Riverbed

10 A Very Simple Experiment

11 It Provokes Interest and Head-Shaking Everywhere

12 The Psychology He Sees Is His Psychology

13 Right on the Threshold to a Better Future

14 The Inkblots Come to America

15 Fascinating, Stunning, Creative, Dominant

16 The Queen of Tests

17 Iconic as a Stethoscope

18 The Nazi Rorschachs

19 A Crisis of Images

20 The System

21 Different People See Different Things

22 Beyond True or False

23 Looking Ahead

24 The Rorschach Test Is Not a Rorschach Test

Appendix: The Rorschach Family, 1922–2010

HERMANN RORSCHACH’S CHARACTER by Olga Rorschach-Shtempelin

Acknowledgments

Notes

Illustration Credits

About the Author

The Rorschach test uses ten and only ten inkblots, originally created by Hermann Rorschach and reproduced on cardboard cards. Whatever else they are, they are probably the ten most interpreted and analyzed paintings of the twentieth century. Millions of people have been shown the real cards; most of the rest of us have seen versions of the inkblots in advertising, fashion, or art. The blots are everywhere—and at the same time a closely guarded secret.

The Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association requires that psychologists keep test materials “secure.” Many psychologists who use the Rorschach feel that revealing the images ruins the test, even harms the general public by depriving it of a valuable diagnostic technique. Most of the Rorschach blots we see in everyday life are imitations or remakes, in deference to the psychology community. Even in academic articles or museum exhibitions, the blots are usually reproduced in outline, blurred, or modified to reveal something about the images but not everything.

The publisher of this book and I had to decide whether or not to reproduce the real inkblots: which choice would be most respectful to clinical psychologists, potential patients, and readers. There is no clear consensus among Rorschach researchers—about almost anything to do with the test—but the manual for the most state-of-the-art Rorschach testing system in use today states that “simply having previous exposure to the inkblots does not compromise an assessment.” In any case, the question is largely moot now that the images are out of copyright and up on the internet. They are easily available already—a fact that many of the psychologists opposed to publicizing the images seem to want to ignore. We eventually chose to include some of the inkblots in this book, but not all.

It has to be emphasized, though, that seeing the images reproduced online—or here—is not the same as taking the actual test. The size of the cards matters (about 9.5″ × 6.5″), the white space, the horizontal format, the fact that you can hold them in your hand and turn them around. The situation matters: the experience of taking a test with real stakes, having to say your answers out loud to someone you either trust or don’t trust. And the test is too subtle and technical to score without extensive training. There is no Do-It-Yourself Rorschach, and you can’t try it out on a friend, even apart from the ethical problem of possibly discovering sides of their personality that they may not want to reveal.

It has always been tempting to use the inkblots as a parlor game. But every expert on the test since Rorschach himself has insisted it isn’t one. They’re right. The reverse is true, too: the parlor game, online or elsewhere, is not the test. You can see for yourself how the inkblots look, but you can’t, on your own, feel how they work.

Victor Norris* had reached the final round of applying for a job working with young children, but, this being America at the turn of the twenty-first century, he still had to undergo a psychological evaluation. Over two long November afternoons, he spent eight hours at the office of Caroline Hill, an assessment psychologist working in Chicago.

Norris had seemed an ideal candidate in interviews, charming and friendly with a suitable résumé and unimpeachable references. Hill liked him. His scores were normal to high on the cognitive tests she gave him, including an IQ well above average. On the most common personality test in America, a series of 567 yes-or-no questions called the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI, he was cooperative and in good spirits. Those results, too, came back normal.

When Hill showed him a series of pictures with no captions and asked him to tell her a story about what was happening in each one—another standard assessment called the Thematic Apperception Test, or TAT—Norris gave answers that were a bit obvious, but harmless enough. The stories were pleasant, with no inappropriate ideas, and he had no anxiety or other signs of discomfort in the telling.

As early Chicago darkness set in at the end of the second afternoon, Hill asked Norris to move from the desk to a low chair near the couch in her office. She pulled her chair in front of his, took out a yellow legal pad and a thick folder, and handed him, one by one, a series of ten cardboard cards from the folder, each with a symmetrical blot on it. As she handed him each c

ard, she said: “What might this be?” or “What do you see?”

Rorschach Test, Card I

Rorschach Test, Card II

Five of the cards were in black and white, two had red shapes as well, and three were multicolored. For this test, Norris was asked not to tell a story, not to describe what he felt, but simply to say what he saw. No time limit, no instructions about how many responses he should give. Hill stayed out of the picture as much as possible, letting Norris reveal not just what he saw in the inkblots but how he approached the task. He was free to pick up each card, turn it around, hold it at arm’s length or up close. Any questions he asked were deflected:

Can I turn it around?

It’s up to you.

Should I try to use all of it?

Whatever you like. Different people see different things.

Is that the right answer?

There are all sorts of answers.

After he had responded to all ten cards, Hill went back for a second pass: “Now I’m going to read back what you said, and I want you to show me where you saw it.”

Norris’s answers were shocking: elaborate, violent sexual scenes with children; parts of the inkblots seen as female being punished or destroyed. Hill politely sent him on his way—he left her office with a firm handshake and a smile, looking her straight in the eye—then she turned to the legal pad facedown on her desk, with the record of his responses. She systematically assigned Norris’s responses the various codes of the standard method and categorized his answers as typical or unusual using the long lists in the manual. She then calculated the formulas that would turn all those scores into psychological judgments: dominant personality style, Egocentricity Index, Flexibility of Thinking Index, the Suicide Constellation. As Hill expected, her calculations showed Norris’s scores to be as extreme as his answers.

If nothing else, the Rorschach test had prompted Norris to show a side of himself he didn’t otherwise let show. He was perfectly aware that he was undergoing an evaluation, for a job he wanted. He knew how he wanted to come across in interviews and what kind of bland answers to give on the other tests. On the Rorschach, his persona broke down. Even more revealing than the specific things he had seen in the inkblots was the fact that he had felt free to say them.

This was why Hill used the Rorschach. It’s a strange and open-ended task, where it is not at all clear what the inkblots are supposed to be or how you’re expected to respond to them. Crucially, it’s a visual task, so it gets around your defenses and conscious strategies of self-presentation. You can manage what you want to say but you can’t manage what you want to see. Victor Norris couldn’t even manage what he wanted to say about what he’d seen. In that he was typical. Hill had learned a rule of thumb in grad school that she had repeatedly seen confirmed in practice: a troubled personality can often keep it together on an IQ test and an MMPI, do pretty well on a TAT, then fall apart when faced with the inkblots. When someone is faking health or sickness, or intentionally or unintentionally suppressing other sides of their personality, the Rorschach might be the only assessment to raise a red flag.

Hill didn’t put in her report that Norris was a past or future child molester—no psychological test has the power to determine that. She did conclude that Norris’s “hold on reality was extremely vulnerable.” She couldn’t recommend him for a job working with children and advised the employers not to hire him. They didn’t.

Norris’s disturbing results and the contrast between his charming surface and hidden dark side stayed with Hill. Eleven years after giving that test, she got a phone call from a therapist who was working with a patient named Victor Norris and had a few questions he wanted to ask her. He didn’t have to say the patient’s name twice. Hill was not at liberty to share the details of Norris’s results, but she laid out the main findings. The therapist gasped. “You got that from a Rorschach test? It took me two years of sessions to get to that stuff! I thought the Rorschach was tea leaves!”

—

Despite decades of controversy, the Rorschach test today is admissible in court, reimbursed by medical insurance companies, and administered around the world in job evaluations, custody battles, and psychiatric clinics. To the test’s supporters, these ten inkblots are a marvelously sensitive and accurate tool for showing how the mind works and detecting a range of mental conditions, including latent problems that other tests or direct observation can’t reveal. To the test’s critics, both within and outside the psychology community, its continued use is a scandal, an embarrassing vestige of pseudoscience that should have been written off years ago along with truth serum and primal-scream therapy. In their view, the test’s amazing power is its ability to brainwash otherwise sensible people into believing in it.

Partly because of this lack of professional consensus, and more because of a suspicion of psychological testing in general, the public tends to be skeptical about the Rorschach. The father in a recent well-publicized “shaken baby” case, who was eventually found innocent in the death of his infant son, thought the assessments he was subjected to were “perverse” and particularly “resented” being given the Rorschach. “I was looking at pictures, abstract art, and telling them what I was seeing. Do I see a butterfly here? Does that mean I’m aggressive and abusive? It’s insane.” He insisted that while he “put stock in science,” which he called an “essentially male” worldview, the social services agency evaluating him had an “essentially female” worldview that “privileged relationships and feelings.” The Rorschach test is in fact neither essentially female nor an exercise in art interpretation, but such attitudes are typical. It doesn’t yield a cut-and-dried number like an IQ test or a blood test. But then nothing that tries to grasp the human mind could.

The Rorschach’s holistic ambitions are one reason why it is so well known beyond the doctor’s office or courtroom. Social Security is a Rorschach test, according to Bloomberg, as is the year’s Georgia Bulldogs football schedule (Sports Blog Nation) and Spanish bond yields: “a sort of financial-market Rorschach test, in which analysts see whatever is on their own minds at the time” (Wall Street Journal). The latest Supreme Court decision, the latest shooting, the latest celebrity wardrobe malfunction. “The controversial impeachment of Paraguay’s president, Fernando Lugo, is quickly turning into a kind of Rorschach test of Latin American politics,” in which “the reactions to it say more than the event does itself,” says a New York Times blog. One movie reviewer impatient with art-house pretension called Sexual Chronicles of a French Family a Rorschach test that he’d failed.

This last joke trades on the essence of the Rorschach in the popular imagination: It’s the test you can’t fail. There are no right or wrong answers. You can see whatever you want. This is what has made the test perfect shorthand, since the sixties, for a culture suspicious of authority, committed to respecting all opinions. Why should a news outlet say whether an impeachment or a budget proposal is good or bad, and risk alienating half of its readers or viewers? Just call it a Rorschach test.

The underlying message is always the same: You are entitled to your own take, irrespective of the truth; your reaction is what matters, whether expressed in a like, a poll, or a purchase. This metaphor for freedom of interpretation coexists in a kind of alternate universe from the literal test given to actual patients, defendants, and job applicants by actual psychologists. In those situations, there are very real right and wrong answers.

Bergdorf Goodman window, Fifth Avenue, New York City, spring 2011 Credit 1

The Rorschach is a useful metaphor, but the inkblots also just look good. They’re in style for reasons having nothing to do with psychology or journalism—maybe it’s the sixty-year fashion cycle since the last burst of Rorschach fever in the fifties, maybe it’s a fondness for forceful black-and-white color schemes that look good with midcentury modern furniture. A few years ago, Bergdorf Goodman filled its Fifth Avenue windows with Rorschach displays. Rorschach-style T-shirts were recently on s

ale at Saks, only $98. “MY STRATEGY,” proclaimed a full-page splash in InStyle: “This season I’m finding myself very attracted to clothes and accessories that have a sense of symmetry. MY INSPIRATION: The patterns of Rorschach inkblots are spellbinding.” The horror-thriller Hemlock Grove, the science fiction cloning thriller Orphan Black, and a Harlem-based tattoo-shop reality show called Black Ink Crew debuted on TV with Rorschachy credit sequences. The video for Rolling Stone’s #1 Best Song of the 2000s and the first single ever to hit the top of the charts from internet sales, Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy,” was a mesmerizing animation of morphing black-and-white blots. Rorschach mugs and plates, aprons and party games are available everywhere.

Most of these are imitation inkblots, but the ten originals, now approaching their hundredth birthday, endure. They have what Hermann Rorschach called the “spatial rhythm” necessary to give the images a “pictorial quality.” Created in the birthplace of modern abstract art, their precursors go back to the nineteenth-century brew that gave rise to both modern psychology and abstraction, and their influence reaches across twentieth- and twenty-first-century art and design.

In other words: three different histories spill together into the story of the Rorschach test.

First, there is the rise, fall, and reinvention of psychological testing, with all its uses and abuses. Experts in anthropology, education, business, law, and the military have also long tried to gain access to the mysteries of unknown minds. The Rorschach is not the only personality test, but for decades it was the ultimate one: as defining of the profession as the stethoscope was for general medicine. Throughout its history, how psychologists use the Rorschach has been emblematic of what we, as a society, expect psychology to do.

Then there is art and design, from Surrealist paintings to “Crazy” to Jay-Z, who put a gold Andy Warhol blot painting called Rorschach on the cover of his memoir. This visual history seems unrelated to medical diagnosis—there’s not much psychology in those Saks shirts—but the iconic look is inseparable from the real test. The agency that pitched a Rorschach-themed video for “Crazy” got the job because singer CeeLo Green remembered having been given the test as a troubled child. Controversy gathers around the Rorschach because of its prominence. It’s impossible to draw a hard and fast line between the psychological assessment and the inkblots’ place in the culture.

The Inkblots

The Inkblots